The Legend of Shigeru Miyamoto

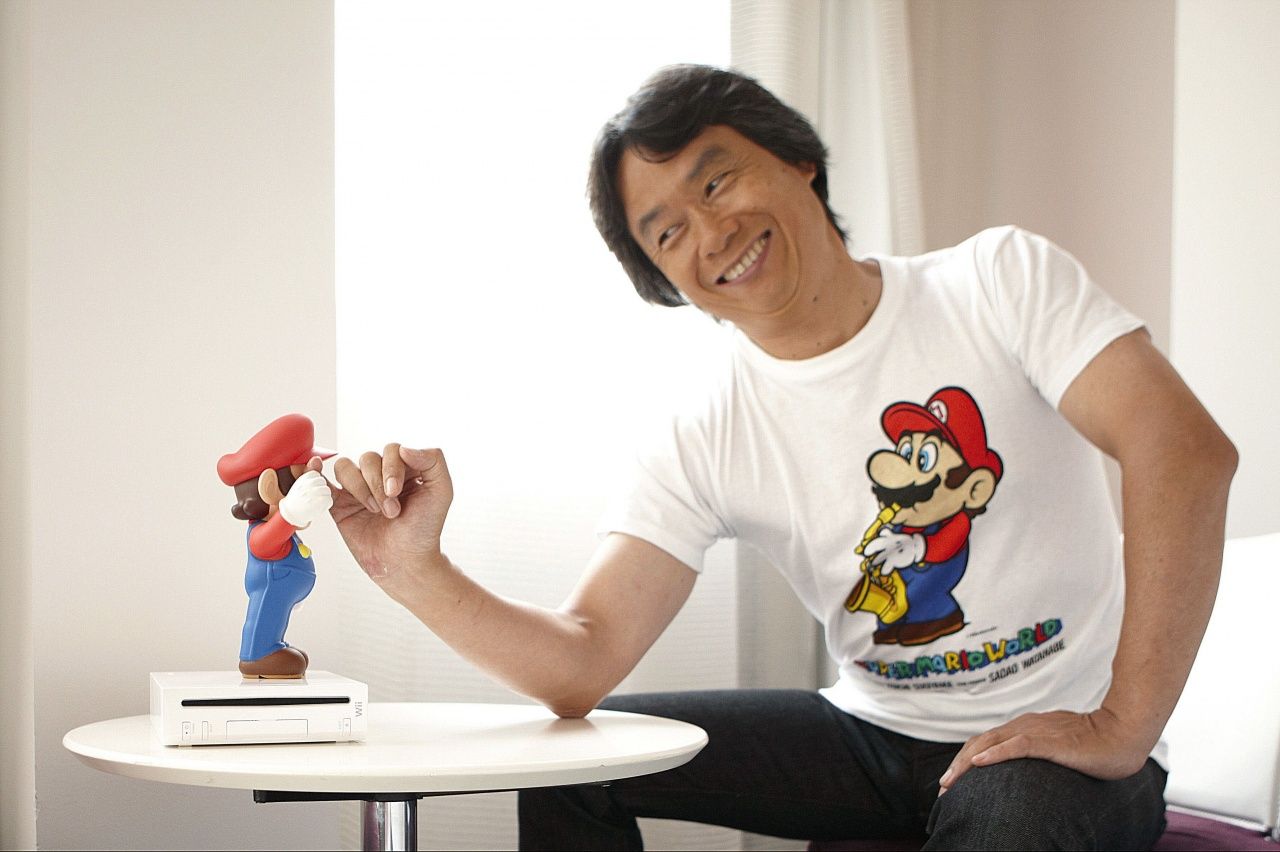

Chances are if you’ve played video games over the last 30 years you’ll recognise this guy. This is Shigeru Miyamoto. Aside from being the closest thing the video game industry has to a rockstar, Miyamoto is also a game designer and producer, and a co-Representative Director of Nintendo. Miyamoto made groundbreaking contributions to the video game industry in its early days, and he is considered one of the pioneering forces behind Nintendo’s success. Name still not ringing a bell? Perhaps you’re familiar with some of his work. Mario. Zelda. Donkey Kong. Star Fox. These are just a few of the many games that owe their legacy to Miyamoto.

Yes, he’s that guy.

Miyamoto’s profound and far-reaching contributions to the world of video games have made him one of the most influential figures in the industry today. Without him, the current landscape for video games would look very different indeed. Praise for Miyamoto comes from far and wide and tends to focus on his dedication to quality over quantity, his considerable work ethic, and occasionally his goofy-yet-adorable personality. But of all Miyamoto’s quirks and talents, perhaps the most revered is his unique approach to game design.

In Nintendo’s early days, Miyamoto crafted his own path in a relatively new industry that mainly relied on technologists rather than artists like himself to create video games. Like an explorer stumbling over uncharted terrain, he approached the design of video games from an entirely new perspective, relying on his background in industrial design to guide him. His approach breathed new life into the relatively homogenous selection of games available at the time. Given Nintendo’s success, evidently it’s not such a bad way of doing things.

Miyamoto has stuck with Nintendo through multiple generations, each one building upon the last. This long history has culminated in Nintendo’s most successful console to date – the Switch. The Switch now has its own formidable library of critically-acclaimed games, with The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild recently being named 2017’s Game of the Year. Countless individuals have been inspired by Miyamoto, and today the video game industry is booming. However, despite the myriad of consoles and games available today, most gamers will admit that playing a Nintendo game feels a little different. There’s something special to it. A charm, a friendliness, a certain playfulness that’s rare to find in other games. But what is this feeling? And how is the development of a Nintendo game different to any other?

In this article we’re going to look at precisely how Miyamoto approaches game design and what we can learn from his personal philosophies. But to understand this, first we need to understand a little about Miyamoto himself.

Miyamoto was born on 16 November 1962 in Sonobe, Japan. He believes he was raised in an advantageous environment. “What I mean by that is, because we didn’t have a car or TV in my home, we had to create our own media to have fun.” As a child, Miyamoto’s first creative endeavours involved making puppet shows based on his favourite comics and movies. From a young age, he entertained himself by bringing the ideas in his head to life. One of these early ideas involved an ordinary guy chasing around a troubled gorilla. Sound familiar? It should! This idea later manifested as the basis for his very first video game.

Some of Miyamoto’s earliest inspirations came from exploring the forests and caves around his home. His fervour for exploration and the heart-racing feeling that accompanied every discovery kept him coming back for more. On one occasion, he took a small lantern from his home in order to explore a dark cave he had discovered. He recalls with clarity the moment he realised that he was standing in a place no one had ever been before. The dual sensations of discovery and accomplishment went on to become driving forces for the development of The Legend of Zelda, and eventually became one of the most crucial aspects of Miyamoto’s design philosophy.

Miyamoto joined Nintendo in 1977 as an apprentice in the planning department. His timing couldn’t have been more perfect. He entered the scene right as Nintendo was branching out from making cards and was starting to develop toys and games. His first assignment was to create a new game to make use of 2,000 unused arcade machines left over from a title which had flopped in the North American market. He claims he was given the job not because of his background in industrial design, but because there was no one else to do it. According to Miyamoto, at the time “the people who made video games were technologists, they were programmers, they were hardware designers. But I wasn’t. I was a designer … I was an artist. I drew pictures.” But video games were moving away from the hands of technologists, and were increasingly falling into the hands of designers like Miyamoto. He embraced the project. And the game he ended up designing? That was Donkey Kong, and it looked something like this:

Miyamoto had high expectations for his game, but was told his design was too complicated to pull off with the technology available at the time. So he stripped down his ideas and created a game based around a single mechanic: jumping. The game featured multiple levels which made use of this jumping mechanic. Accordingly, the playable character earned the name Jumpman, although it was eventually changed in the American release to Mario, after Mario Segale, the landlord of Nintendo’s warehouse. The design philosophy Miyamoto employed in Donkey Kong – focusing on a single mechanic and exploring how to make it as fun as possible – is another crucial aspect that shows up time and time again in his work.

Donkey Kong was a success. This opened the door for Miyamoto to continue creating games, including for Nintendo’s first home console: the Nintendo Entertainment System or NES. He created two games with vastly different approaches: a linear, side-scrolling game called Super Mario Bros., and a nonlinear game called The Legend of Zelda. The impact of these two games was monumental. They tightened Nintendo’s grip on the home console market and set the company on a path that would transform the game industry forever.

But why was the NES so successful? After all, gaming was already widespread at the time, and home computers were the obvious choice for gamers. So why go out and purchase a NES? Well, a lot of Nintendo’s success is thanks to the games themselves, which were only available on Nintendo’s console. But this just raises another question, one we’ve been asking for decades: What did these games do differently? Over the years Miyamoto has given us some interesting insights into how he designs games. So now, finally, we have gained an understanding of what gives Nintendo games that special charm.

The Secrets of Game Design According to Shigeru Miyamoto

Part One – The Basics; Level 1-1

I try to avoid all trends.

I’m the kind of person who doesn’t want to be told to do something because “that’s the way you do it.”

The line of thinking represented in Miyamoto’s quotes above is still prevalent in Nintendo’s ethos today. While other game developers may have moved towards implementing online capabilities, improving graphics and sustaining additional entertainment services on their consoles, Nintendo’s hardware has infamously always been relatively stripped-back and somewhat limited. What Nintendo products may lack in technical prowess, however, they make up for with their true focus: making fun games!

For Miyamoto, this is the true purpose of a good game. His intent is to provide players with the opportunity to achieve something in the games they are playing. In order to do this, it comes down to two things: conveying to the player what they need to do, and immersing the player in the game. Accessibility and immersion. These are the cornerstones of Miyamoto’s design philosophy. However, with the limited technology available in the days of Super Mario Bros., game designers needed to come up with creative ways to present players with an accessible and immersive game. This is where we begin to see some of these clever design choices come into play.

Does this look familiar? This is level 1-1 of Super Mario Bros. It’s the first thing players see. It’s a fairly innocuous setup. But when players pick up the game for the first time they may not be familiar with the mechanics, so they need to learn how to play. And what better way to learn than through experience? The layout above may appear fairly simplistic, but even this first screen alone is bursting with intelligent design choices, all of them perfected by the developers after running repeated simulations to ascertain what actions the player might take. The final result is a finely-tuned level in which nearly every design choice facilitates learning how to play. So how is it done? Let’s take a look in a little more detail.

The tricks begin right off the bat. Mario’s positioning on the left side of the screen (as opposed to his regular position in the centre) is no mistake. The open space to the right encourages players to begin moving in that direction. Almost immediately they bump into a Goomba. Is it friend or foe? New players may not know. At first glance, this may seem like a cruel choice, but it’s actually designed to help players figure out what hazards are present in the world as soon as possible. If Mario bumps into this cheeky little Goomba, the penalty is negligible. Players are simply returned to the beginning of the level, and now they’ve learned what they need to avoid. Next time, they’re likely to either jump over the Goomba to escape it, or jump onto its head to kill it. Either way, the level’s design has accomplished the goal of teaching players how to detect and dispatch enemies without a single word, and it has also introduced the game’s key mechanic (and Mario’s main ability): jumping!

Having bypassed the first of many Goombas, players now turn their attention to the blocks. Notice how the gold question-mark blocks draw your eye? They’re designed to be interesting to players, encouraging them to interact with them. Once Mario hits the first block, players are rewarded with a coin, furthering their desire to find out what’s inside the other blocks. The next question-mark block reveals a mushroom. Miyamoto explains in the interview above that, even if players are cautious of the mushroom following their experience with the Goomba, this section of the level practically ensures the mushroom will hit Mario whether they like it or not. As a result, Mario grows bigger, the players are happy, and the concept of power-ups has been explored.

Finally, there’s the B-Dash. The segment you can see above allows players to experiment with the B-Dash in a safe environment before putting their skills to the test by leaping over a bottomless put. By the time players clear this jump, they have essentially completed the tutorial and are familiar with everything they need to know to play the game!

In this way, Level 1-1 is designed so that players learn how to play organically while still enjoying the game. Miyamoto usually designs these levels later in the development process specifically to act as a tutorial, without detracting from the element of fun.

So that just about covers accessibility. What about immersion?

Given that Super Mario Bros. is a 2D game with a simplistic, side-scrolling interface, it might be considered overkill to think about how to immerse the player in the game. But not for Miyamoto. Mario’s slippage was added as a way to add weight to the character which, in turn, helps players form an emotional attachment. By injecting the game with this additional dose of realism, the developers found a way to make players feel connected to the character in the game. This slippage is tweaked in every Mario game to date by an internal team to ensure players feel connected and involved with the game they are playing.

Miyamoto’s enduring dedication to manufacturing player-friendly experiences lives on to this day in subsequent Mario titles, as well as countless other Nintendo games. His enthusiasm for this approach can be seen here where he encourages young players testing out Mario Maker for the Wii U, urging them to “add mushrooms at the beginning of the level to help players out.” You’ve got to admit, his dorky persistence to making levels player-friendly is admirable. In the case of Super Mario Bros., Miyamoto’s focus on accessibility and immersion resulted in a game that was easy to pick up and play, and gave players a sense of accomplishment at the end of each level.

Part Two – Form Follows Function

We get the fundamentals solid first, then we do as much as we can with that core concept as our time and ambition will allow.

I think they first discover an interesting theme to work on and, only afterward, determine that they should focus upon the specific audience in order to work on the theme, not vice versa.

These kinds of messages tend to crop up in every Miyamoto interview in some form or another. What they tell us is that Miyamoto prefers to approach game design with a focus on creating interesting mechanics rather than pandering to an audience and allowing trends to define or alter the creator’s vision. In essence, this philosophy reflects a principle in industrial design known as Form Follows Function. What this means is: how something looks should be determined by how it works, and not the other way around. This reflects Miyamoto’s preference for fully developing gameplay mechanics before ascribing design details.

Take Splatoon for example. Before the conceptualisation of Inkopolis, Inklings, or the punk-rock aesthetic, the developers envisioned a game purely about shooting and swimming through ink. While this mechanic was developed and expanded upon in early tech demos, there were no characters and no setting; the game consisted of featureless cubes moving about the screen shooting ink in barren test stages. Initially, when the developers were struggling to come up with a character, Miyamoto even suggested using Mario!

Eventually they settled on the quirky Inklings we know and love today, but long before these characters and the setting began to take shape, the developers focussed purely on perfecting the gameplay mechanics of shooting ink. Over time, this single mechanic began to inform additional design choices. Weapons recharged by swimming through ink. Inking a wall could be used to climb up it. It was a natural leap to draw connections between ink and graffiti, and in turn the punk-rock aesthetic. This is a flawless example of Form Follows Function, and highlights the focus on creating fun and engaging gameplay first, and only then expanding on the design.

It’s come a long way.

A similar process occurred with the game Pikmin. Miyamoto got the idea for Pikmin when he was gardening with his wife one day. It began as a relatively simple concept: collect Pikmin, throw them, and call them back. From this, enemies and challenges were introduced, differently coloured Pikmin were given unique characteristics and, by the third game, players controlled three characters independently of one another. Pikmin is another typical example that shows how Nintendo prefers to focus on introducing a core concept and expanding on it, inventing new and interesting ways for players to use it, rather than reusing concepts because it’s easier.

Of course, it’s not Miyamoto alone responsible for making all these games. It takes a lot of work and dedication from an extensive team of game developers to bring a project to fruition. These days, Miyamoto’s duties are concerned with overseeing the development of these games and ensuring Nintendo’s standards are maintained. Miyamoto makes sure to foster a positive, creative atmosphere to support his design teams. “I try to encourage directors to have courage and work towards the goal they set, and pose questions to them about whether the game is actually delivering the experience to the player as envisioned.” By highlighting the design team’s personal investment in the products they are creating, Miyamoto reduces the gap between developers and players; both parties are supposed to love the game, after all. In addition, Miyamoto believes that “if development of products that thrive on creative uniqueness is dictated by those who prioritise sales and profits, the possibilities for the future of entertainment will be limited.”

Frame that one and put in on your wall.

On top of all this, Miyamoto is known for pushing the boundaries of current technology and looking for new and exciting ways to enhance gaming. That’s not to say that Nintendo always gets it right, but it’s telling of Miyamoto’s philosophies that Nintendo was the first to implement shoulder buttons on their controllers with the SNES, the first to introduce motion controls with the Wii, and the first to create a hybrid home/portable console with the Switch. Rejecting trends, highlighting accessibility and immersion, and crafting games the developers themselves love. If you’re looking for the answer as to why Nintendo’s games have that special charm to them, I think we’ve found it.

Part Three – Super Mario Odyssey; A Case Study

Times have changed since the days of Super Mario Bros, and so has game design. The constant evolution of new technology makes it easier than ever to create bigger and better games. It begs the question: Is Miyamoto’s approach to game design still relevant today? And, if so, is it still applied to modern Nintendo games? To answer this question, we’re going to take an in-depth look at the newest Mario game for the Nintendo Switch: Super Mario Odyssey.

First, let’s look at accessibility. Given the development of technology, when talking about accessibility now, it’s important to not only discuss how easy it is to figuratively pick-up-and play, but also how easy it is to literally pick up and play. With the Nintendo Switch’s option to play on the TV or in handheld mode, it’s more important than ever for the controls to be accessible so you can play on the train or at the airport just as easily as you can at home. Despite Mario’s extensive moveset in Odyssey, most essential controls are limited to the control stick and two buttons – one to jump, and one to throw Mario’s hat. This makes sense, given Odyssey is essentially a game about throwing Mario’s hat. I think it’s fair to say that’s a pretty accessible control scheme.

How about the core mechanics? Earlier entries in the main series of Mario games focussed on our favourite plumber’s trademark jumping ability, but recent entries typically include an extra feature to build on the established mechanics and add a new challenge. In Super Mario Sunshine it was FLUDD. In Super Mario Galaxy it was the spin attack. Now, it’s the hat throw.

Super Mario Odyssey was built around this mechanic, and Mario’s new ability is incorporated into every aspect of the game’s design. Mario uses his hat to attack enemies, open doors, hit blocks, jump further, collect coins and, of course, to possess the enemies and objects that inhabit the world. The seamless integration of the new mechanic makes the hat throw as intuitive as jumping was in earlier Mario titles. Plus, in typical Nintendo fashion, it adds something new for veterans to play around with. Each possession adds a unique challenge and a new experience for players. Despite the huge number of possessions, none feel unnecessary and each serves a purpose. While some are used for navigating platforming challenges and attacking enemies, others are used to enhance the player’s ability to get around quickly and easily (for instance, possessing a Cheep Cheep in a water level). With hundreds of moons to collect in Odyssey, not a single opportunity is wasted when it could potentially offer a fun and rewarding experience for players. It’s obvious that the designers put player-friendly gameplay with a focus on fun first.

As such, it stands to reason that if Super Mario Odyssey is built on the principle of Form Follows Function, then the way the game looks should be a direct result of the way the game is played. This approach has been confirmed by Odyssey’s director, Kenta Motokura, who explained that while they were coming up with prototypes, they were also considering the locations that would lead to the most fun ways to experiment with it. “For example, if we came up with a gameplay idea that kind of required ice or snow, maybe a slippery surface, we would have to think that would be fun to use in a place that had ice or snow.” These early considerations of the areas that ultimately became the game’s kingdoms are only the beginning. Nearly all aspects of the game’s design was informed by this core mechanic. Hats can represent an enemy’s health, or indicate whether something or someone can be possessed by Mario. A race of sentient hats inhabits one of the game worlds. The Odyssey is in the shape of a hat. This sort of cohesion is a clear indication that the game was brought together with a core concept in mind that informs all other parts of the game.

I don’t know about you, but to me it seems like Nintendo’s still using the same old tricks to make new Mario games.

Applying Miyamoto’s Design Philosophies

It goes without saying that Miyamoto’s game design philosophies have been a recipe for success. That’s not to say that Nintendo hasn’t received its fair share of criticism over the years. Nintendo games are often criticised for having outdated visuals, or for being too childish, or even for leaning too heavily on novelties and gimmicks such as touch screens and motion controls. There’s validity in these concerns, but notice how they tend to focus on superficial aspects? Despite this sort of criticism, it’s rare to see a review that says the latest Mario game isn’t very fun, or the most recent Zelda title feels unfinished and lacking polish. Nintendo games may not always live up to fans’ expectations, but I think it’s fair to say that the bar is set extremely high, and it’s not often that Nintendo releases a first party game that is considered substandard. At the core of all Nintendo games, Miyamoto’s design philosophies still shine through. For game designers, artists, or anyone with a dream or passion, there are a couple of worthwhile lessons we can take away from Nintendo’s enduring success.

A game needs a sense of accomplishment. And you have to have a sense that you have done something, so that you get that sense of satisfaction of completing something.

Miyamoto’s initial goal when setting out to create a new game is to give players a sense of accomplishment. Inseparably intertwined with this goal is the need for players to want to achieve something. This is accomplished by presenting players with a game that is easy to understand and that they are motivated to play. Some developers accomplish this by focussing on a particular theme, feeling or plot device. For instance, horror games are designed to scare players, to elicit a feeling of fear. Here, gameplay might take a back seat to the development of atmospheric and sound design. A narrative-focussed games tells a story, presenting characters whose own thoughts and feelings guide the progression of the game. Nintendo games, on the other hand, tend to spurn such concentrations in favour of placing fun as the driving force at the centre of the game.

It’s not to say that one way is right and the other is wrong; the difference is in the kind of response these games aim to elicit from players. Nintendo games infamously feature minimalistic plots, highlighting gameplay elements over rich narratives. Players are given an opportunity to craft their own stories, experience their own sense of discovery, and are guided by their own curiosity while playing. The sense of accomplishment gained in such a game isn’t represented through a scripted cinematic sequence, but rather comes from the players own thoughts and feelings. In the same way that Miyamoto urges his design teams to make games they love rather than something that will sell, players are encouraged to experience the game in their own personal way, without explicitly being told how they should feel. It’s for this precise reason that immersion is so important in Nintendo games. Characters like Mario and Link remain mostly voiceless so that players can place themselves in the heroes’ shoes, and work towards accomplishing their own goals, rather than the goals of characters in a fabricated story.

A good idea is something that does not solve just one single problem, but rather can solve multiple problems at once.

We’ve seen that Miyamoto prefers to focus on a single, new gameplay mechanic to drive the production of a game. Often, expanding on a simple idea is more advantageous than stringing together numerous, complex ideas. Beginning the development process with the plot or setting first and working backwards to implement interesting gameplay elements means attempting to retroactively shove what is essentially the core of the game – what the players actually do – into predetermined boxes.

Nintendo works from the opposite angle. Nintendo’s approach provides creators with limitless freedom to expand on what makes the game fun rather than enclosing it within the confines of a plot or setting. (This is why we have such a convoluted timeline for the Zelda series!) Nintendo isn’t alone in this development process, and it’s easy to tell when game designers have taken a similar approach. Miyamoto himself praised Valve’s Portal as a “great game,” for building its premise around a single elegant mechanic: the portal gun. A more recent success story is the critically acclaimed Mario + Rabbids: Kingdom Battle for Switch, developed by Ubisoft. The creators obtained Miyamoto’s blessing to use Mario in the game by attempting something new – something that hadn’t been seen on a Nintendo console before. The surprisingly seamless integration of tactical battles taking place in a version of the Mushroom Kingdom overrun by Rabbids is a perfect modern example of adapting and expanding upon established styles of gameplay to create something entirely new. The creators’ love for the game shines through at every turn, evident in the call-backs to both Mario and Rabbids franchises, the esoteric jokes and the reimagining of enemies and locations.

Ideally we should be making things that can be enjoyed by the widest possible range of people.

Over the years Miyamoto has touched on how the final polish to a game can make a world of difference to the finished product. He has expressed that they weren’t confident that Breath of the Wild would be successful until they were putting the final touches on the game. However, he has also expressed that, if it came down to it, time spent enhancing the graphics or implementing cinematics should be sacrificed to fine-tune the core mechanics of a game to ensure that they operate flawlessly. When all is said and done, perhaps Miyamoto’s game design philosophy can be summarised as one of those expressions that we’re all already familiar with: It’s not what’s on the surface that counts, but what’s inside.

By encouraging designers to pour their spirit into the games they are making, by highlighting the importance of core gameplay mechanics, and by making games that he would personally enjoy, Miyamoto’s guidance has ensured that the games produced by Nintendo are, first and foremost, loved by the creators, long before that same adoration spreads to gamers. By embracing new technologies, pushing boundaries, and focussing on what is new and unique rather than trendy and profitable, Nintendo games today continue to possess the same charm they did in the early days of video games. Is it too much to suggest that if we all took a lesson out of Miyamoto’s book and focussed on embracing simplicity and creating things that we are truly proud of, we would have more products that glow with that special Nintendo charm? I don’t think so.